A film with an evocative title, The Brutalist, and an Oscar win for its protagonist, Adrien Brody. It might seem like yet another consecration of a “brute” aesthetic, now mainstream and reduced to mere style. But Architectural Brutalism is much more than a raw concrete facade. Born from the ashes of World War II, this controversial movement has marked the urban landscape of the 20th century with imposing buildings, often criticized for their austere monumentality, yet bearing a profound ethical and social message, and a search for truth and authenticity that deserve to be rediscovered. Let us prepare to go beyond the concrete shell and investigate the precious core of Brutalism, a movement that, behind its brutal facade, conceals a pulsating heart of ideas, ideals, and humanity. This is Brutalism, according to PulpVanilla.

Brutalist Anatomy: Exposed Concrete, Naked Functionality, and Truth of Materials

Brutalism is not a style, it’s an attitude. An ethic, even more than an aesthetic, as its proponents liked to repeat. Born in the United Kingdom in the 1950s, in an era of post-war reconstruction and radical rethinking of the role of architecture in society, Brutalism presents itself as a reaction to nostalgic sentimentalism and superfluous ornamentation that had characterized previous architecture. Watchword: honesty. Structural honesty, material honesty, functional honesty.

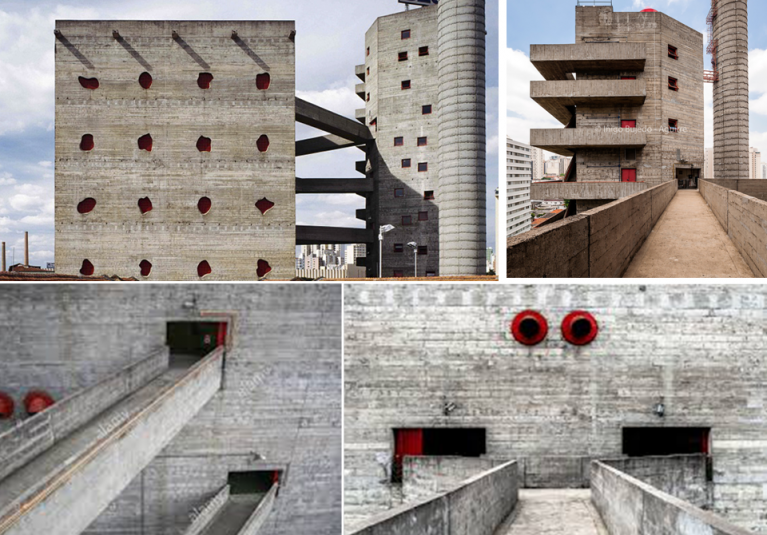

Exposed concrete, béton brut to put it in French, becomes the quintessential material, exhibited in all its raw materiality, with the imperfections of the pour, the rough textures, the traces of the construction process deliberately left visible. But not only concrete. Brick, often left unplastered, steel, glass, wood, also contribute to defining an essential and sincere material vocabulary, which rejects elaborate finishes and decorative masks.

Brutalist forms are solid, geometric, often monumental, composed of pure and angular volumes that interlock and overlap in sculptural compositions. Structural expression is fundamental: pillars, beams, slabs, stairs, become protagonist aesthetic elements, exhibited with pride and clarity. The modularity and repetition of constructive elements create rhythm and order, but without falling into tedious seriality, thanks to the variety of textures and the plasticity of concrete.

Functionality is the guiding principle: “form follows function” – the modernist motto that Brutalists take up and push to the extreme. Interiors are often bare, essential, minimalist, favoring practicality and efficiency. The goal is to create useful, solid, durable buildings that concretely respond to the needs of the community, without aesthetic compromises or concessions to bourgeois taste.

Roots in Modernism, Look to the Future: Origins and Historical-Social Context of Brutalism

Brutalism is not born from nothing. It has its roots in the Modern Movement, particularly in the work of Le Corbusier and the philosophy of the Bauhaus. From these movements it inherits the attention to functionality, the use of modern materials, the rejection of historical styles, and the ambition to create an architecture for all, democratic and socially responsible.

But Brutalism is also a reaction, a critical overcoming of Modernism itself, perceived by some as too cold, abstract, rationalistic. Brutalists seek a truer, more human, more rooted architecture in the social and material context. Hence the choice of poor materials such as raw concrete, the valorization of texture and materiality, the emphasis on structure and functionality without compromise.

The historical context is crucial: Brutalism emerges in the post-war period, in an era of reconstruction and profound social and political changes. The need for low-cost housing and efficient public buildings pushes towards rapid, economical and honest construction solutions. Reinforced concrete, a versatile and democratic material, becomes the ideal answer.

But there is more: Brutalism also embodies a utopian and radical spirit, a desire for tabula rasa and reconstruction from the foundations not only of cities, but of society itself. In an age of ideological crises and social unrest, Brutalism presents itself as a committed architecture, which rejects compromise and rhetoric, and aspires to represent a new social order, more egalitarian, more authentic, more brutal in the sense of sincere and unadulterated.

Masters of Concrete: Brutalist Hall of Fame and Iconic Works

If Brutalism were a religion, Le Corbusier would be its prophet. Works such as the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille(1952) and the Capitol Complex in Chandigarh (India, 1951-1961) are true manifestos of the movement, anticipating and defining the Brutalist canons: exposed concrete, bold geometric forms, integration of different functions in a single building, search for new forms of collective living.

But the true theorists and gurus of Brutalism are perhaps the British Alison and Peter Smithson. Their Hunstanton School (1954), essential and skeletal like a functional diagram, and the controversial Robin Hood Gardens residential complex (demolished in 2017, not without controversy), are works that codified the Brutalist aesthetic and spread its word throughout the world.

Another undisputed master is the Hungarian-British Ernő Goldfinger, best known for his Brutalist residential towers in London, such as Balfron Tower and Trellick Tower (1972), imposing, controversial buildings, often perceived as menacing, but in reality animated by a social ideal and a search for dignity for the working classes.

The American Paul Rudolph, with his Yale Art and Architecture Building and the Boston Government Service Center , brings Brutalism to the United States, interpreting it in a more sculptural and plastic key, with corrugated surfaces and complex and articulated forms.

The Brazilian Lina Bo Bardi, with SESC Pompéia in São Paulo (1986), a cultural and sports center converted from a former factory, demonstrates how Brutalism can integrate with local culture and a humanistic approach to design, creating lively, welcoming, and popular spaces, despite the apparent coldness of concrete.

And how can we forget the Canadian Moshe Safdie and his Habitat 67 in Montreal (1967), a utopian and visionary residential complex, composed of prefabricated concrete modules assembled in a chaotic and organic way, which anticipates themes such as prefabrication, modularity, and the search for new forms of collective living.

Beyond Architecture: Brutalism in Design, Graphic Design, Web Design. The “Brute” Aesthetic that Conquered the World

The influence of Brutalism is not limited to architecture alone. The brute aesthetic, the emphasis on functionality, the rejection of ornament, have also infected other design fields, from graphic design to web design, to industrial design and furniture.

In graphic design, Brutalism translates into essential and raw layouts, bold and legible typography, limited color palettes, use of basic shapes and material textures. An anti-decorative and functional aesthetic, which prioritizes the clarity of the message and communicative strength over formal beauty.

In web design, Brutalism manifests itself as a reaction to the sleek and standardized aesthetics of the mainstream web. Brutalist websites are distinguished by essentiality, simplicity, absence of frills, prevalence of text, use of monospace fonts and raw and asymmetrical layouts. An aesthetic that rejects the conventions of polished web design, and that aims for functionality, accessibility, and direct communication. Iconic examples are websites such as Craigslist or early versions of Google , essential, functional, and brutally effective.

Also in industrial design and furniture, Brutalism leaves its mark, with massive and monolithic furniture, made of raw and unfinished materials such as concrete, rustic wood, untreated steel. An aesthetic that privileges the truth of materials and structural solidity, over formal elegance and decorative refinement.

Criticism, Controversies, Re-evaluations: Brutalism Today. A Counter-Current Legacy, Still Alive and Stimulating

Brutalism has always been a controversial movement, which has aroused conflicting passions: love and hate, admiration and repulsion. Criticized for its coldness, its inhumanity, its oppressive monumentality, often associated with authoritarian regimes or “barracks” of public housing, Brutalism was progressively abandoned starting in the 1980s, supplanted by styles that were lighter, more decorative, technological, and in line with public taste.

Yet, in recent years, we are witnessing an unexpected rebirth of interest in Brutalism. An unexpected and counter-current revival, fueled by several factors:

- Nostalgia for an authentic and sincere era, in which architecture still had an ethical and social dimension, before the spectacular and consumerist drift of contemporary architecture.

- Appreciation for the honesty and materiality of Brutalism, in an increasingly virtual and immaterial world. Raw concrete, with its rough and true texture, becomes an antidote to the falsity and superficialit of the digital world.

- The influence of social media and visual culture, which have rediscovered the iconic strength and photogenicity of Brutalist buildings, transforming them into viral memes and cult objects for a new generation of architects and designers.

- The contemporary reinterpretation of Brutalism by young architects, who take up its essential principles and materiality, but integrate them with new technologies, new materials, and an ecological and sustainable sensibility.

Brutalism, therefore, is not “dead and buried.” It is a movement still alive and stimulating, which continues to question us about the role of architecture in contemporary society, about the relationship between form and function, about the truth of materials, and about the need for an ethical and socially responsible architecture. A “brutal” legacy, perhaps, but precious, which deserves to be rediscovered and valued.